Best of 2010: Film

This list is pretty accurate to how I feel now, I’d definitely move up Inception though.

10

Inception

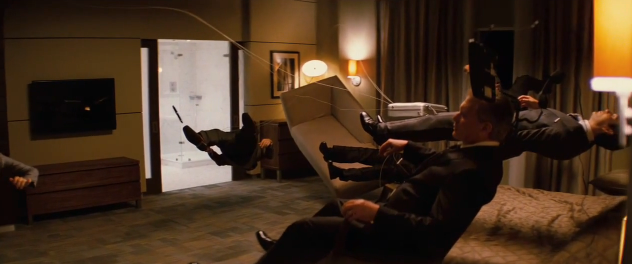

A complex, far-fetched sci-fi thriller that is a hit with audiences? Impossible, unless you are Christopher Nolan. As a director who has become famous for breaking the rules of storytelling in Memento, he approaches Inception with the same level of mystery and distance. Inception’s brain-twisting concept of dream invading and idea stealing/planting is as bizarre as they come, especially for a tent-pole summer blockbuster, and in many ways Nolan succeeds more in the action than he did in the brain-twisting. Initial viewings of Inception are full of bewilderment of what is going on and a rewarding sense of understanding as the mechanics of this world are unfolded in endless exposition heavy sequences that are actually rewarding because Nolan set up his puzzle to appear illogical, so when logic is then supplied to the audience it makes you feel like a genius. However, returning to Inception, the cracks become incredibly clear; it’s suddenly obvious where Nolan expects the audience to be confused, where he plans to reveal the logic of it, and where concepts bump heads and sort of slip off stage hoping the set pieces will keep you distracted. Fortunately, they do. Inception is undeniably unique and several of the unique action sequences redefine what these kinds of scenes should look and behave like, the most obvious being the uneven-gravity hotel hallway.

Nolan’s version of the dreamscape also defies convention by being pristine opposed to hazy, operating with a strict set of rules instead of without any. Nolan’s worlds all operate under similar constraints because aside from being a filmmaker, he is a puzzle master, and therefore must have complete order to pull the strings and make his illusions pop. Nolan knows how to reward his audience, which is why he is so adored in Hollywood, so by applying his many rules to Inception he is able to successfully pull of one of the most prohibited endings in any form of storytelling. After all, it is more rewarding to debate and argue endlessly when there are laws to apply, rather than randomness subject to the authors mind. Inception is a bit of both, which is why it’s so brilliant.

written by Christopher Nolan; directed by Christopher Nolan.

9

The Fighter

Oh, what’s this, a boxing movie about an underdog who takes one last stab at a title shot? It sure sounds familiar, and it is. Despite the fact that The Fighter should be as irrelevant as vampire movies by now, it manages to find a way to squeeze into the already populated world of terrific boxing movies. Despite being nothing new narratively, The Fighter win based on character rather than ingenuity. From it’s opening scene, where Christian Bale fidgets through an interview, looking like his face has melted as he portrays a crack addict named Dickie, it’s clear that a terrific amount of effort went into this production. Mark Wahlberg called this film his dream project which he kept alive for years while deals fell through, and it shows. Wahlberg, who has been on an unfortunate cold streak since The Departed must have been saving all his energy for this role, where he doesn’t give scene stealing performances like some of his co-stars but has the subtle emotional core to the story. Director David O. Russell makes a pivotal decision to extend the story beyond the family and incorporate the community that Micky (Wahlberg) represents, a decision that some community-rooted films such as The Town failed to capture authentically. From the energetic opening one-take where Russell freely follows Micky and Dickie through their neighbourhood interacting with everyone from shop clerks to drug dealers there is a solid sense of place in a larger world that this film roots itself in. By walking the audience through the community, we see the world on a grander scale and how small Micky is in contrast, as well as how far he has to go. This dedication to the community of Lowell gives The Fighter the gravity it requires to make Micky’s rise compelling despite the fact that so many stories have told us the same thing before.

written by Scott Silver, Paul Tamasy, Eric Johnson; directed by David O. Russell.

8

Scott Pilgrim vs. The World

Despite booming into the entertainment industry’s most profitable division, video games have completely and utterly failed to transition to film despite a wealth of worlds to mine from. Although Scott Pilgrim vs. The World is an adaptation from a graphic novel series, both the books and the movie have deep roots in video game iconography, culture, and lore to the point that it could be argued that Scott Pilgrim is the first successful video game movie ever — perhaps because it chooses to steal the energy of these games rather than their convoluted plot lines. Although it takes place in some form of “reality”, Scott Pilgrim vs. The World moves at a breakneck pace between video game in-jokes, soapy teen romance, sitcom punctuation, and anime-inspired, gravity-defying battle sequences that ignore any form of logic and end with everyone going to Pizza Pizza for a bite to eat. The film runs like some sort of inverse avante-garde stream of consciousness film you’d see at an art house theatre, but instead of being inside the mind of an insightful artist, we are inside the mind of a directionless, ADHD-riddled, twenty-something slacker whose nostalgic appreciation for pop culture is a flawless match with nostalgic pop culture extraordinaire Edgar Wright. Scott Pilgrim is absolutely a dividing experience, it has to be to work at all. It speaks to a very specific audience who understand growing up in the early 1990’s and who understand current alternative music culture — although it could be argued that these references and in-jokes fly by at such a pace and with such casual indifference that someone unfamiliar with them could miss them and not even notice, instead picking up on the more obvious jokes.

On second thought, maybe Scott Pilgrim is more accessible than I am giving it credit for. It is a movie for the elitist hipster who takes pride in getting every passing reference, it is for your gamer nerd who likes seeing fight scenes with large low-res pixels, and for you indie music scene advocates who like movie-long jokes about selling out. For a movie that is as unapologetically juvenile, Scott Pilgrim vs. The World is surprisingly layered and unlike any film in 2010… or ever.

written by Edgar Wright, Michael Bacall; directed by Edgar Wright.

7

True Grit

The Coen brothers are two of the most compelling directors in Hollywood, constantly escaping definition and who are perhaps most well known for their elaborately detailed narratives and ability to jump between genre seemingly at will. That is exactly what distinguishes True Grit from most Coen films, for once in a long time it seems like the Coens have comfortably nestled into a single genre, rather than eluding them all.

To Coen fans, the brothers are also well known for their consistent ability to churn out exceptional performances from their actors whether it be capping the volcano that is Nicolas Cage in Raising Arizona, keeping John Turturro on the right side of narcissistic in Barton Fink, or transforming Javier Bardem from pretty boy to sadistic otherworldly monster in No Country For Old Men. In True Grit, the majority of the film is a three-character adventure where Jeff Bridges, Matt Damon, and Hailee Steinfeld exercise their acting ranges in what feels like an actors playground. Bridges gets to play up his theatrical eye-patch-wearing presence with an appropriately worn accent who sees the details of law and order as an inconvenience to his business of headhunting; Damon plays an eccentric Texas Ranger with a glowing sense of pride in his uniform, his state, and his country; while newcomer Steinfeld has the insanely good fortune of landing her first major role under the Coen brothers as a firm, naive teenager who personifies the fast, complicated transition from child to adult.

Despite the puzzling “supporting” actress Oscar nomination, Hailee Steinfeld is the core of this film who is out to avenge her father’s murder. Away from home she is shooed off by busy and unsympathetic government men and business owners, but acting as some sort of apparition of women of the late 20th century, Steinfeld shows refusal to be ignored or talked down to by the men who “run” the chaotic early days of America. This leads her to Rooster Cogburn, the symbol of all that is filthy about men yet she sees a glimmer of goodness in him and makes it her goal to mine it out. The film hits a lot of familiar notes about optimistic innocence spreading to the more cynical, in return for life lessons from those more experienced, but the main theme to take away seems to be the degeneration of childhood. Steinfeld comes to town equipped with a lawyer when everyone else has revolvers, witnesses public hangings of crying men, and spectates but does not participate in several gun fights. These wearing experiences happen in an instant as the result of her fathers death which turn a simple farm girl into a world weary woman. Although the film resolves with Steinfeld receiving no more respect than she entered with, the experience defines maturity not on age, but on experience.

written by Joel and Ethan Coen; directed by Joel and Ethan Coen.

6

The King’s Speech

The King’s Speech from afar looks like any other award-baiting period piece with fancy costumes and stern, nationalistic themes and characters, yet somehow, despite having many of these things, The King’s Speech evades this dismissive definition. What defines The King’s Speech is its willingness to open up dramatically and balance silly comedy with solemn historical gravity. The King’s Speech, like most solid historical dramas, gets enough right that its historical liberties are acceptable casualties to strengthen its characters and script. Yes, King George’s stammer is exaggerated and yes, the timeline is condensed, and yes, his brother is drawn in antagonistic wide strokes. Yet, The King’s Speech never crosses the line to cartoonish melodrama because the main focus is firmly held with the growing relationship between King George and his speech therapist Lionel Logue as well as an examination of George’s lonely and painful childhood filled with illness and social rejection by both his peers and family making it a rare costume drama that offers a critical appraisal of aristocracy rather than simply congratulatory. Although the story follows King George VI, the audience constantly is in the same position as Lionel, learning more about George whenever he cares to open up. There is a great satisfaction in seeing a serious figure not only in this film, but in history, loosen up behind close doors and begin a cursing rampage. The King’s Speech manages to shatter the tough exterior of a historic leader, turn him into a clown, but maintain his dignity as a sympathetic character and inspiration.

written by David Seidler; directed by Tom Hooper.

5

Animal Kingdom

This gritty crime family story lets its ensemble of terrific character actors sharpen their teeth on tough, dark material that we didn’t get in North America this year. Brutally unrelenting; a tragic family portrait of a modern age gone awry.

written and directed by David Michôd.

4

Certified Copy

Is the recreation as valid as the original? This transcending conversation piece blends different ideas together in powerfully simplistic ways that are so effective, yet obvious in hindsight, it strikes you as “no shit, why didn’t I think of that?!” storytelling. Masterful.

written and directed by Abbas Kiarostami.

3

Toy Story 3

Hats off to Pixar for continuing to achieve success in their films and by continuing to push the notion of “children’s film” out the window. Like last year’s Up, Pixar has once again taken a colourful, family-friendly story and injected serious emotions and themes that make the film sometimes uncomfortable, well uncomfortable for a “children’s film”. Proving there is room in animation for serious discussions about growing up, moving on, friendship, and even life and death, Toy Story 3 probably takes the largest leaps in this regard of the entire trilogy, but it still retains the bright spirit and memorable cast of the previous films. Plotted as a partial homage to The Great Escape, Toy Story 3 follows Woody and Buzz as they attempt to traverse a shockingly oppressive daycare after being abandoned by their owner Andy. Similar to Toy Story 2, there are toys with hidden agendas, but for the most part, the additional cast is joyous and welcome to the mix, particularly the Ken doll who acts as Barbie’s counterpart as a metrosexual fashion diva. Toy Story 3’s gags and adventures sometimes drive a bit too far from their humble origins of trying to get from a pizza place or apartment building to home in the previous films, but largely Toy Story 3 is as good and in many respects better than it’s predecessors making this one of the rare trilogies that ends as strongly as it began. More importantly, it is yet another Pixar film that speaks to kids on an intelligent level while engaging them with laughs — at this point it is as though Pixar has to remind everyone else every single year that this is possible.

written by Michael Arndt; directed by Lee Unkrich.

2

The Social Network

Much lauded and derided for its machine-gun paced dialogue, what The Social Network lacks in authenticity it makes up for in pure entertainment value. A film about the creation of Facebook, and the world’s youngest billionaire, The Social Network uses gorgeous high definition video cinematography, focused performances, and rousing dialogue to deliver a story of the ironies of a business devoted to revolutionizing friendship and connection while its main players each become more alienated from each other. The entire film has a rogue, “fuck you” rhetoric in the name of institution and business where creating something new and revolutionary trumps making business deals and money. Facebook creator Mark Zuckerberg (played by Jesse Eisenberg) tells his potential colleagues that he declined selling an application he created to instead release it online for free, giving only a passive shrug as explanation for why. Despite their rebellious attitude to new age business, the people this story circles each become engulfed by the rifts business makes in personal relationships which develops the inter-cutting plot between Zuckerberg and two different parties suing him in federal court: one his former (and only) best friend, the other a pair of twins who feel cheated by Mark’s invention. Facebook is about putting everything about your friends online, while these characters desperately try to keep everything about each other offline. The film is largely dialogue driven, but the outstanding cinematography makes it a gorgeous work to stare at with textured environments balancing the “antique” feel of Harvard with the “glossy” feel of Facebook and stunning depth of field tricks making each shot beautiful. The photographic look of the film could be distracting if it were not for Fincher’s extreme focus on his subjects where conversations are largely pointed towards the listener and each terrific performance is given through subtle nuances of facial expression. The dialogue might get all the attention in The Social Network but the physical gestures of their responses drive the performances in equal measure.

written by Aaron Sorkin; directed by David Fincher.

1

Exit Through The Gift Shop

Beginning as a rather formulaic yet perverse examination of street art culture and ending as a critique on art in general, Exit Through The Gift Shop is unexpectedly vast in scope which could derail the movie but it’s tight focus and smart segway from the emerging street art culture as a whole to one filmmaker turned artist draws interesting parallels towards Andy Warhol and modern art. Specifically, the process in which the work is created and the sometimes overly eager public ready to embrace anything new without discretion are points of criticism and observation. Subversive street artist Banksy takes the directors chair to define and highlight the difference between a movement that was once highly condemned to the modern multi-million dollar institution in an effort to define the difference between street art and meritless graffiti. The film offers no definition but does highlight the thin line between the two and how easily they can be misconceived. The original street artists with a statement are being arrested; while the new-age gallery graffiti artists looking for press and making “limited” pieces via paint splatter become millionaires.

It has been suggested that the film is an elaborate hoax, which Banksy denies and doesn’t change the films impact either way. It’s deceptive qualities make the experience more perplexing rather than distracting like the more gimmicky “faux-or-not-faux” documentaries bombarding cinemas. Banksy’s message to the world remains the same, as one user on the always tasteful YouTube community pointed out on the film’s trailer: “This movie just took a massive beer shit on all the snobby art buyers and trendy hipsters.” It’s funny because it’s true.

directed by Banksy.

Honourable Mentions

I was really surprised by The Town this year. Ben Affleck’s directorial debut was surprisingly solid in Gone Baby Gone, yet the third act began to spiral with plot twists, Affleck goes dangerously in the opposite direction by making a fairly by-the-books heist film. There aren’t really any surprises to The Town but it’s aided by a solid supporting cast made up by Jeremy Renner, John Hamm, and Chris Cooper as well as outstanding direction from Ben Affleck. It takes a lot of cues from earlier heist films, the right kind that show it’s a movie with a lot of heart behind it rather than a generic rip off. There is a lot of humor and personality to the film, though I do wish that more time was given to develop the actual town of the movie.

Another solid film this year that didn’t quite make my list is Winter’s Bone. It’s brutally real and honest in it’s depiction of low income communities, the struggles to stay on a good path, and representing true catch-22 situations. The plot is a bit loose for my tastes, where young Jennifer Lawrence (who deserves the Oscar) wanders fairly aimlessly from house to house of characters who may have wandered out of Deliverance or The Texas Chain Saw Massacre asking for her father — of course it doesn’t help that her father cooked meth with all his friends who are all tweaked out from cooking and smoking their product. It’s a grisly tale that doesn’t shy away from showing the poor realities some people face and the lack of support that their government, police, and education systems will provide. Some people seem to have no luck, but Winter’s Bone maintains a certain level of positive outlook finding contentment in family and perseverance.

Worst Movies of the Year

Coming soon! I promise!